I have just returned from a vacation, interluded by a couple of trips – one of them to DEFCON, the world’s largest hacker conference. This year, it ran at the Riviera hotel and casino in Las Vegas at the beginning of august.

There was plenty to see and do, from conferences as interesting as war-rocketing to an insight into the US-VISIT program, and it’s plans to implement RFID tags into the green visa waivers, or the 2D barcode receipts given out at airports.

I participated in the wardriving events, organised by Thorn, and which consisted of the Running Man and Fox Hunt competitions. Our team was led by Renderman, and we had some backup that put up some noise (fake APs, floods, etc.) to make the contest more interesting.

The Running Man started well, but unfortunately the other team tripped casino security by walking past their booth with a magmount omni antenna on each shoulder, a laptop, several WiFi cards dangling from their belts, a YellowJacket, and other gear – apparently, the IT guys freaked out, and they wanted the contest shut down. After the intervention of Ross and Priest, we were allowed to carry on, but limiting the search area to the venue, and not the whole casino. After the contest resumed, we found the Running Man in around 15 minutes, and won!

The second contest, Fox Hunt, consisted of a hidden WRT54G that was only on for 15 seconds every minute. One was supposed to locate the fox, connect to it, and change the SSID after brute-forcing admin account. 15 seconds to do all that is not a lot! So, our plan was to locate the fox….and make a run with it to a safe place, so we could kill the 15 second timer circuit, reduce the amount of RF leaking out and have a go at changing the SSID. The first part of the plan went well, but then the other team got slightly miffed, called Thorn, who in turn called us to go back to the contest table with the WRT so the other team could also have a go at it.

Interestingly, Thorn had taped the admin password to the bottom of the router, but neither team noticed it! In fact, the other team ended up brute-forcing the AP and changing the SSID. We contested that since when we removed and reapplied power to the AP, the SSID went back to its default, we had in fact won, but Thorn wasn’t having any of it. The contest was a tie, which was decided by the question “Who owns the OID 00:00:00?”, the answer to which is Xerox. We got it wrong, and so we lost. Next year we will be better prepared for sure.

Here are a few pictures from the event:

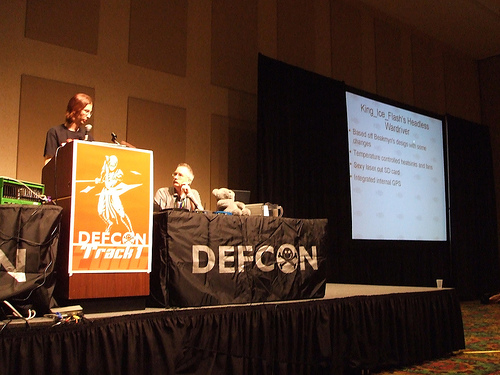

Thorn and Renderman giving their presentation on the Church of Wifi, with CoWPatty, the WPA rainbow table generator, and the WRT54G mods, which included my WaRThog.

The war-rocketing guys, and their awsome rocket. I wonder how they got that thing past airport security.

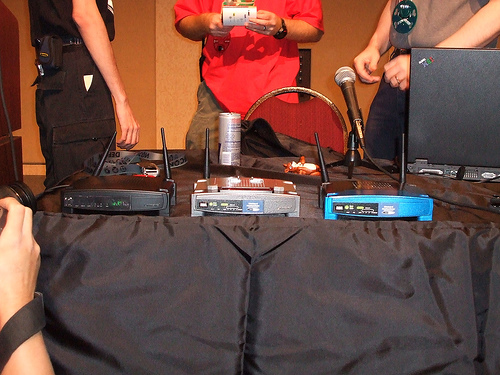

The WaRThog on the left, with two more of CoWF’s modified WRT54Gs.

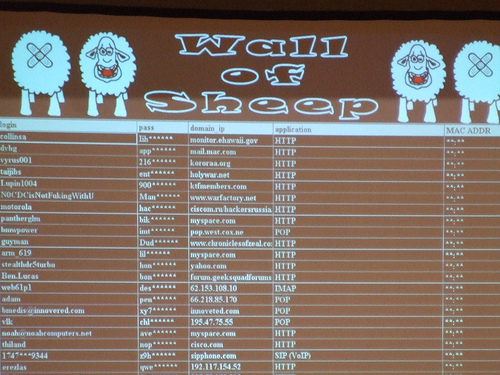

If you used DEFCON’s wireless network to check your email, access your corporate network, etc., but didn’t use any form of security (VPN, SSH…), you are bound to be in the Wall of Sheep. It displays captured user names, passwords, domains and access methods – I actually had the two colleagues travelling with me show up here, even though I told them to not even open their laptops while at the con.

See you next year!